Indian legend has it that centuries before the white man came to what is now southwestern Illinois, a giant bird with antler-like horns, horrible red eyes, a somewhat human face, a body covered with scales, and a long serpent-like tail cruised the skies in search of prey.

So large and powerful was this beast that it easily could carry off a grown deer or even a man in its terrible claws. It would terrorize the Indian villages by descending unexpectedly on a tribe and carrying off its victims to a cave in the Illini bluffs, where it would devour them. The Indians called the creature the Piasa (pronounced PIE-a-saw) or "bird that devours man."

The beast defied hundreds of attempts by the Indian warriors to kill it. Entire villages were nearly wiped out, and fear spread throughout all the Illini tribes.

The courageous Chief Ouatogo, fearing for the safety of his children, fasted in solitude and prayed to the Great Spirit - the Master of Life - to protect his people from the wrath of the Piasa.

On the last night of his fast, the Great Spirit came to Ouatogo in a dream and instructed him to select 20 of his warriors, each armed with bow and poison arrow, and hide them in a designated spot. A lone warrior was to stand in plain sight as a victim for the Piasa. At the instant the bird pounced on its prey, the warriors were to shoot their arrows. When the chief awoke the next morning, he thanked the Great Spirit, and told his tribe of the dream. The warriors were quickly selected and the ambush was set according to the instructions in the dream.

Ready to die for his tribe, Ouatogo offered himself as the victim. He stood in open view of the bluff and soon saw the Piasa perched on the cliff, eying its prey. The chief summoned all his courage, stood boldly erect, and began to chant the death song of an Indian warrior. The Piasa flew into the air and, swift as a thunderbolt, descended upon the chief. When the beast reached its victim, every bow was sprung as planned and each arrow found its deadly mark in the Piasa's scaly body. The bird uttered a wild, horrible scream that resounded across the land, and died.

But not one arrow, not even the bird's terrible claws, had touched Ouatogo. The Master of Life, in admiration of the generous deed of the chief, had held over him an invisible shield. In memory of the event, the tribe painted an image of the Piasa on the face of the bluff near where the city of Alton, Ill., stands today.

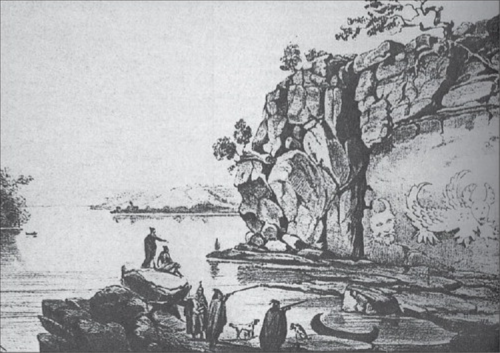

Just a legend? Maybe. But the image of the bird on the bluff is real enough and has endured for centuries. Explorer Jacques Marquette first sighted the painting In 1673 during his journey down the Mississippi River.

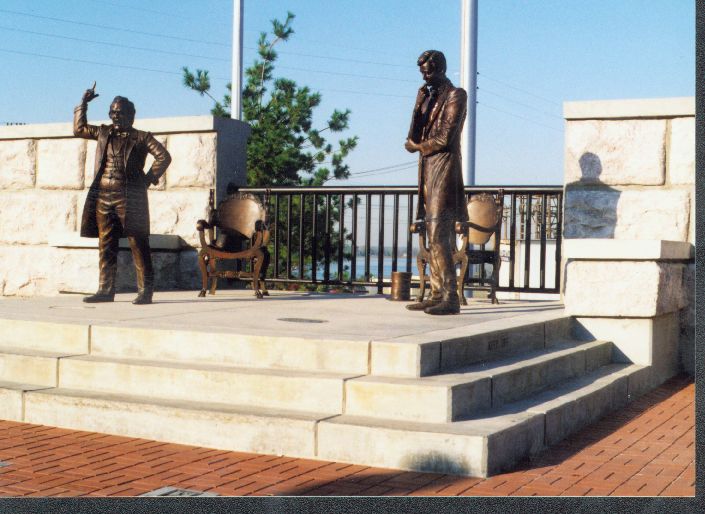

Today, if you drive along the Great River Road near St. Louis you will see a red, green, and yellow bird painted on the face of The bluff above the Mississippi River just west of Alton, Illinois.

In 1984 a 9000 pound steel sculpture of the Piasa Bird was mounted to the bluff face at Norman's Landing and was removed some years later. This steel sculpture was placed under the present Clark bridge in Alton until it was discovered by a student at Southwestern High School. Since their mascot is the Piasa Bird, the school purchased the steel sculpture for $1.00, hauled it to their school, repainted the sculpture and erected it along side the football field along route 267 just north of route 16 and 267 junction in Macoupin County.

Thanks to the restoration efforts of the Alton-Godfrey Rotary Club, the Illini Indian legend of the "bird that devours man" lives on.

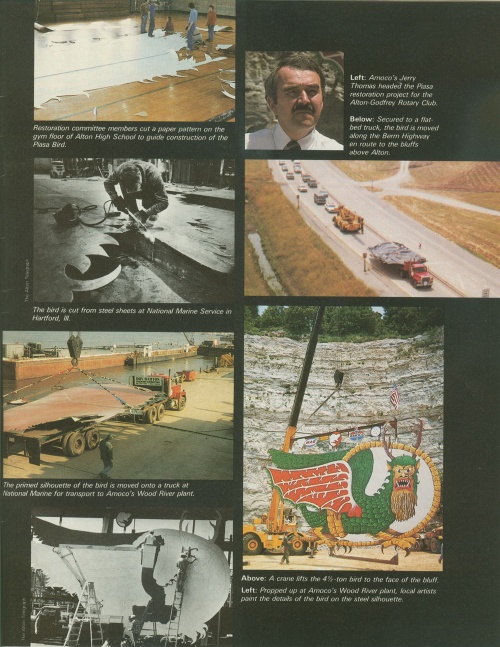

Jerry Thomas, director of employee relations for Amoco Petroleum Additives Company's plant in Wood River, chaired the Rotary's Piasa Bird restoration committee. "The Piasa Bird is a deep-seated tradition in the Alton area, and people here take great pride in it," Thomas says. "School children all know the legend of the Piasa Bird."

For centuries, abundant shrubbery and trees protected the image of the bird from the elements. But after the arrival of settlers, several fires laid waste the protective cover, causing the limestone to crumble.

The Alton community repainted portions of the bird on the bluff many times, but the limestone caused the paint to fade rapidly. Merely repainting the image on the bluff was rejected by the Rotary's restoration committee as not being permanent enough.

The club developed a plan to paint the bird on an aluminum sheet and bolt it to the bluff. The cost of the project was estimated at $50,000.

The Rotary members' fund-raising efforts included offering "Restore the Piasa" buttons for $1 each;selling T-shirts, sweatshirts, and booklets that recount the Piasa legend; and sponsoring events such as a midget-car race and a mountain-music show. A "color the bird" contest helped arouse interest, and local clubs, businesses, and industries were canvassed for contributions.

But because of a faltering economy, the Rotary's efforts raised only $12,000-far short of the needed $50,000. With cost ruling out aluminum, the Alton-Godfrey Rotary turned to a second option&emdash;steel.

The club approached the National Marine Service in Hartford, Ill., which not only offered to donate the steel, but the labor as well. Rotary members provided the pattern and National Marine cut the outline from sheet steel.

"Things began to fall together then," Thomas says. "After fabrication, we needed a place to store the giant bird." This problem was solved when Amoco offered a space at its Wood River plant to store the bird upright, ready to be painted.

Once it was stored, a slide was made of a picture of the bird, and the image, enlarged to the full 23-by-40-foot size of the steel plate, was projected onto the pattern. The steel plate was primed twice with special paint, and nine local artists spent a combined 400-500 hours painting the colors and filling in the details.

While the painters were at work, Rotary members, under the direction of Rotarians and Alton businessmen Bill Moyer and Jim Hernandez, investigated ways to secure the 4 1/2-ton bird to the bluff. "Again, local businessmen came to our aid by donating the manpower and equipment to drill the holes needed to bolt the bird to the cliff," Thomas says. "Others cleared the site, donated the fuel for the equipment, and a local construction company volunteered its 55-ton crane to hoist the bird into position. Rotary members helped with site cleanup, landscaping, and the like."

A special permit from the Illinois Department of Transportation was required to haul the bird along the Berm Highway from the Amoco plant to the bluff. State Rep. Jim McPike and State Sen. Sam Vadalabene helped expedite that process, Thomas says, and the Alton and Wood River police departments provided the highway escorts.

In all, more than 250 people, and 40 area firms and organizations donated time, resources, and money so that the Piasa Bird would once more stand sentinel on the Illini bluff. Thomas estimates that 1,480 volunteer man-hours and 500 hours of equipment use went into the 18-month restoration project.

A performance of the Piasa Indian Dancers during the dedication ceremony help celebrate the conclusion of a more than year-long volunteer effort coordinated by the Alton-Godfrey Rotary Club.

To honor the efforts made by the members of the Alton-Godfrey Rotary Club, and the area residents and businesses, the Illinois Legislature passed a joint resolution of general recognition of the Piasa restoration project. The bluff is now marked as an official state historical site.

"The thing that excited me was how the project kept snowballing," Thomas says. "The spirit of the people-the stuff of legends-matched the spirit of those prehistoric Indians who long ago spoke in awe of the power of the Piasa."

And perhaps centuries from now, the story still will be told about how a dedicated group of people banded together to keep a legend alive.

(Article by Joe Massucci reprinted from the July/August 1984 issue of Amoco Torch)

This early drawing of the Piasa Bird, one of Alton’s favorite legends, was done by the German artist/scientist Henry Lewis after he toured the Midwest in the 1850s. It is one of the most important early works on the Mississippi. The Native Americans seem to be on their guard. According to legend, no Native American ever journeyed up or down the Mississippi without shooting arrows and, later, firearms. Drawing of the Piasa from Henry Lewis’ Das Illustrite Mississippihal published in 1858.

.png)

.png)